To our surprise, the Mexican and US results were virtually identical, which suggests that music-to-color associations might be universal. To study possible cultural differences, we repeated the very same experiment in Mexico. Meanwhile, the angriest-sounding music elicited the angriest-looking colors (dark, vivid, reddish ones). We compared the results and found that they were almost perfectly aligned: the happiest-sounding music elicited the happiest-looking colors (bright, vivid, yellowish ones), while the saddest-sounding music elicited the saddest-looking colors (dark, grayish, bluish ones). We’ve tested our theory by having people rate each musical selection and each color on five emotional dimensions: happy to sad, angry to calm, lively to dreary, active to passive, and strong to weak. They may not know that they’re doing this, but the results corroborate this idea. If colors have similar emotional associations, people should be able to match colors and songs that contain overlapping emotional qualities.

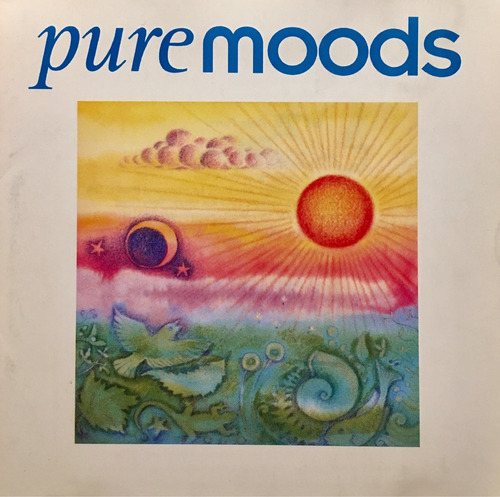

(Why this might be the case is something we’ll explore later.) C sounds angry and strong, and D sounds sad and calm. In the four clips you just heard, selection A “sounds” happy and strong, while B sounds sad and weak. We believe that it’s because music and color have common emotional qualities. The mediating role of emotionīut why do music and colors match up in this particular way? Meanwhile, selection D, a slow, quiet, “easy listening” piano piece, elicited selections dominated by muted, grayish colors in various shades of blue. Selection C was an excerpt from a 1990s rock song, and it caused participants to choose reds, blacks and other dark colors. Selection B, a different section of the very same Bach concerto, caused participants to pick colors that are noticeably darker, grayer and bluer. Selection A, from Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto Number 2, caused most people to pick colors that were bright, vivid and dominated by yellows.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)